Tattooing in Australian Prisons

‘When I used drugs and alcohol, I did crime. They went hand in hand.’

Unfortunately for Johnny ‘halves’ (selling half caps of heroin at full price earned him his nom de guerre), his drug debts became insurmountable, and he found himself casing a bank situated conveniently down the road from his Perth house.

After hastily devising a plan with two mates, they jacked themselves up on amphetamines, stole a car, parked it behind the bank, and drove another vehicle to procure various items. They returned to the bank and stormed through the front doors donned in wigs, hoodies, sunnies, and sawn-off shotguns.

‘People went running each and every way, including the tellers, who ran out the back.’

After forcing the sole remaining teller at gunpoint to hand over his float, they scurried out the back and into their vehicle for the short getaway drive home.

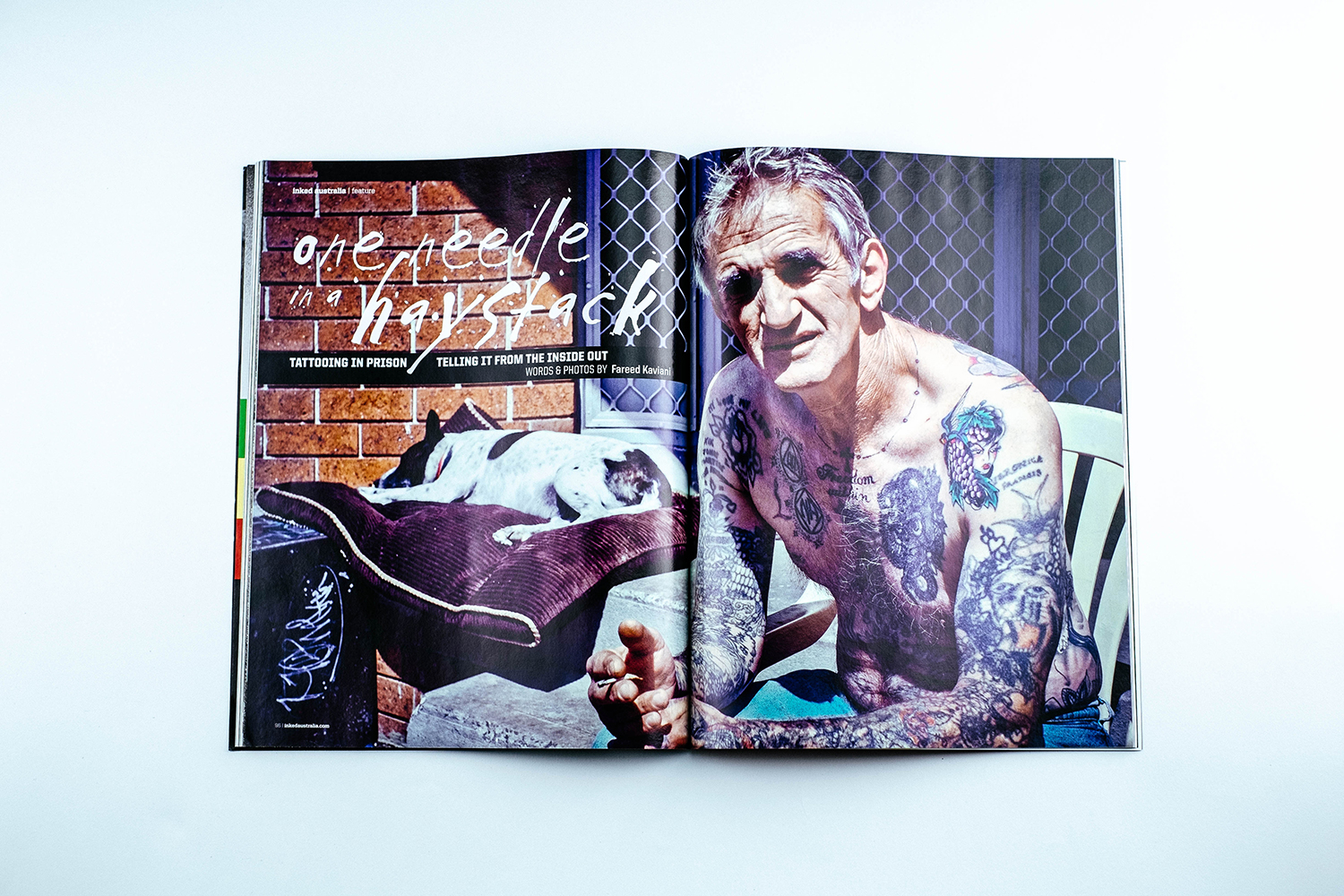

Johnny 'Halves' with his dog, Dylan.

Back at Johnny’s, they counted the paltry loot. Around four, five grand. From the massage parlour next door, a girl strolled in to buy a hit. Before being told to fuck off, she noticed, through the cacophony of police sirens, an inordinate amount of cash and weapons strewn upon the coffee table.

A few minutes later, police raided the house and arrest the three of them.

‘They cuffed me and covered me head with a jacket. When they was walking me to the car I peeped my head up, and you know what I saw? The girls from the massage parlour lined up across the road looking all sexy in their lingerie!’

‘But you know, I can’t really remember much of it, I was jacked up and pilling off me head.’

This was in 1991. Today, Johnny sits at a café down the road from his Melbourne home to discuss with me his time in various prisons across Australia.

‘Bail was set at $10,000. No one bailed me out. Eight months later I was sentenced to seven and a half years. I went to Freemantle prison but the conditions were terrible and eventually it closed, so I was sent to Casuarina. Then there was Bunbury, Pardulap, Albany, and Canningvale, where I was in the slot for twenty-three hours a day, and then back to Casuarina.’

‘It’s another world in prison, there’s dos and don’ts out here, and then there’s dos and don’ts in there. The prison officers have control, but the prisoners are trying to have control, so there’s constant friction. You could fight it or just go with the flow. I used to just go with the flow, and do tattoos.’

Johnny would tattoo people for extra smokes as well as draw up designs for everyone just to pass the time. All of his prison tattoos distinguish moments during his incarceration, he tells me. Often, these moments are quite macabre.

‘Like I did that one in J division,’ he said while pointing to a tattoo of prison bars, ‘I ended up in the psychiatric division. You know, having drugs every day for four years and then all of a sudden no drugs, I was gone; I was hearing ants fart.’

When he arrived in J division, an inmate approached and asked if he would kill him for a pack of White Ox tobacco.

‘That was his way of finding out if I wanted to hurt him or not. Another guy was so messed up he chopped his own dick off. The medical staff sewed it back on so he thought, I’ll show you, and chopped it off again and flushed it down the toilet!’

Johnny 'Halves'.

Owing to a dearth of academic studies, acquiring conclusive quantitative data on the frequency of tattooing in Australian prisons is beyond the bounds of possibility, especially given that tattooing in Australian prisons is illegal. If inmates are discovered giving or receiving tattoos, internal disciplinary processes are adopted.

Such disciplinary processes were enforced against Johnny.

‘It was to my understanding that tattooing was considered defacing government property. So when the prison officers caught me, I was sentenced to serve seven more days. But that didn’t stop me. I used to love tattooing in jail. Loved it. Especially when I got away with it. The prison staff can’t control it; it’s a culture thing.’

Although prisoners were often caught in the act and stripped of all tattooing contraband, the prison officers were regularly outsmarted.

‘Just to smuggle ink in, people would put it up their arse. If there wasn’t ink, we’d burn rubber from a shoe, burn it to a crisp, put some water in it, sometimes I’d even spit in it, mix it up: and you’ve got your ink. Or you could use charcoal. The machine was made from cassette player motors, a toothbrush, a button, a biro case, and a sewing needle. That needle would be used on up to twenty people.’

This extremely unhygienic method exposed prisoners to noxious infections.

‘It’s all about getting the ink in, and keeping it in. If it gets infected, you can’t seek medical attention because you’re not allowed to get tattoos.’

The quandary was recognised by The Burnet Institute’s 2011, in its evaluation of drug policies and services at the Alexander Maconochie Centre, an Australian correctional facility located in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT).

The report found that 40 per cent of the prison’s tattooed inmates had been tattooed while incarcerated, and records of sharing needles and ink were very high. It stated that tattooing in prison represents a unique combination of risk factors for blood-borne virus transmission because it is illicitly performed by untrained operators with homemade, unsterile, and frequently shared equipment.

Its recommendation to combat and reduce the spread of disease was simple: provide a safe tattooing service for inmates.

In 2012, the ACT’s health minister, Katy Gallagher, said she believed a safe, professional tattooing service could be effective in bringing an end to the spread of blood-borne diseases in incarcerated populations.

Today, however, harm-reduction measures are yet to be put into place in any Australian prison. A spokesperson for the health minister informed me that ‘although the ACT government takes the responsibility for care of prisoners seriously and is committed to providing the most appropriate health care and interventions…, the government has [still] not made any decisions relating to the introduction of a professional tattooing program.’

The spokesperson added that, if the program were to be approved, the focus of its modus operandi would be to reduce blood-borne viruses.

Johnny's Ned Kelly tattoo.

I believe that, with the introduction of a safe tattooing program, it is myopic to focus exclusively on mitigating blood-borne viruses. All Australian prisons, and many around the world, run vocational education and training programs as part of a prisoner’s rehabilitation. As well as providing technical skills, these courses improve communication and organisational skills, and they reduce the likelihood of recidivism. These programs focus primarily on blue-collar industries; yet, with a large clientele at his disposal, Johnny, not to mention the whole prison community, would have benefited from a holistic tattoo program in which he had been professionally trained.

In a controlled environment, gang tattoos could be managed, the unnecessary spread of disease would cease, stricter punitive measures could be enforced for those who perform tattoos outside of the program, and people like Johnny could improve on or gain new skills.

‘When I got out of prison, I had these grand plans of opening a tattoo studio, but I ended up with my own lawn-mowing company. Now that I’m out, I do tattoos at my house as a hobby. I love it. I get excited. I’ve got guys who used to be in prison would come over to get the ones they got done inside covered up. Just because they’re different people now, they want it covered.’

‘I just do them for fifty bucks an hour, but sometimes, if I see me mates, I tell them to stay clean for six months and I’ll do them one for nuthin.’

Photos taken by Fareed Kaviani.