Initiation: An Ancient Ritual in a Modern World—Samoan Tatau.

‘He starts by marking you off. All you feel is the bull tusk scratching you. Then he tells you to get on your stomach and lie on a pillow that’s like a rice bag, so it’s difficult to breathe. Then, each of the four guys takes hold of a limb; the fifth guy is there as the main stretcher. Then the tufuga [tattooist] says in Samoan, “Okay bro, hang in there. What you’re going to go through is a lot of pain, but it’s important that you commit to it and don’t pull back. Everybody is here with you. The spirits are here with you. All of Samoa is with you.” This is when it starts. The first hit goes along your spine. After that all you hear is tap tap tap tap tap … for the next five days.’

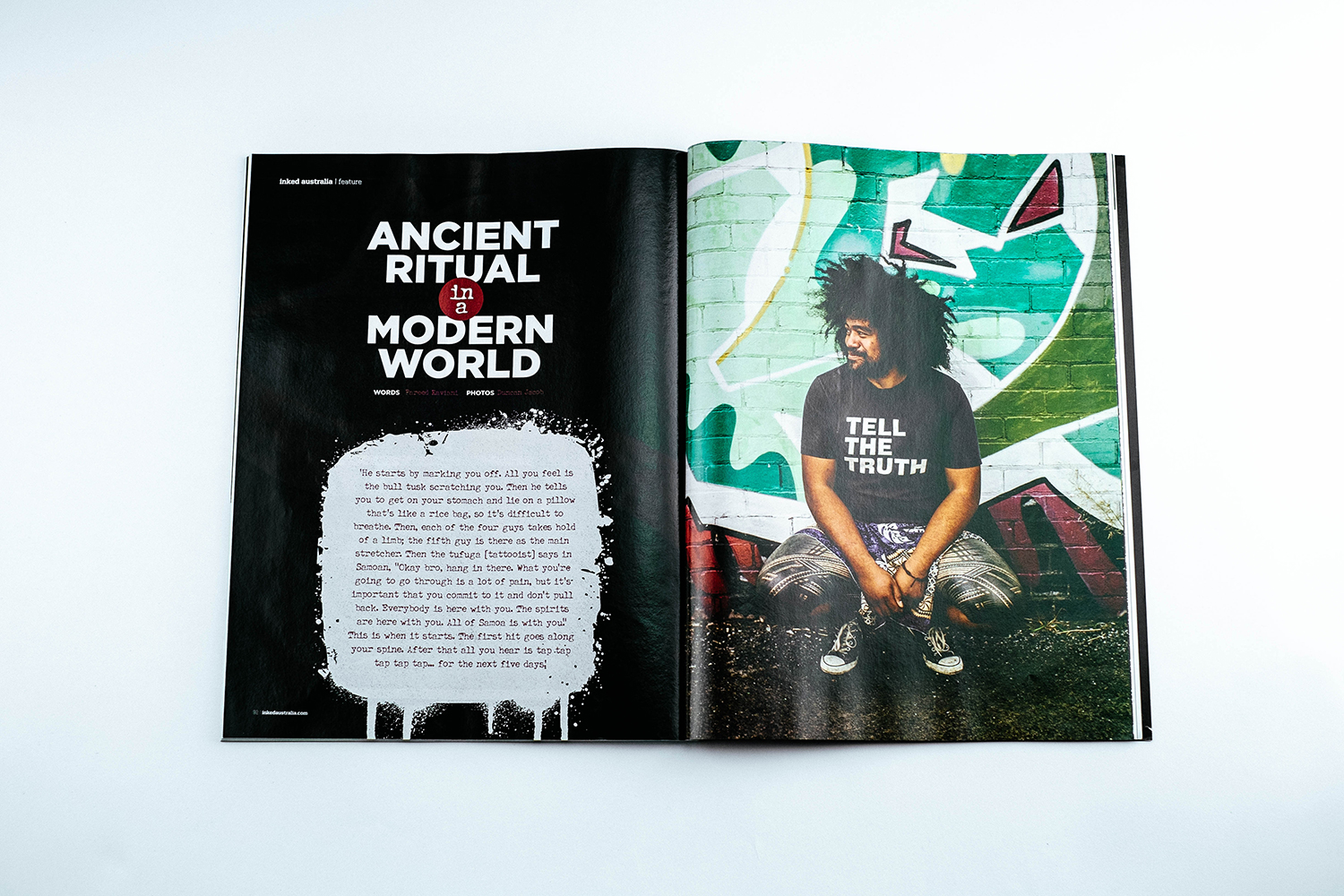

Chris Lemuelu (photo taken by www.duncographic.com).

Samoa is an idyllic group of Polynesian islands in the South Pacific, which Germany, the United States, and Britain all fought to dominate during the late 19th century. The Tripartite Convention of 1899 eventually brought an end to this war of deluded entitlement, partitioning the islands into two, with America annexing the eastern island-group, which is still known as American Samoa. Control of Western Samoa was divided between the two remaining belligerent nations. Not too long after, Britain abandoned all claims to Samoa, and, on the 29th of August 1914, New Zealand invaded, with Germany’s complicit acquiescence. Although the occupation was ‘peaceful’, New Zealand imported a strain of pneumonic influenza that wiped out one-fifth of the population. From the end of World War I to Samoa’s independence in 1962, New Zealand remained its imperial ruler. In 1997 the state constitution was amended to change the country’s name from Western Samoa to Samoa. Through European methods of trade and communication, the colonial powers of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries introduced new technology, languages, religion, culture, and ideologies that transformed Samoa in many ways. Samoan people were, however, very active in shaping these ‘western’ imports, and, despite centuries of European influence, tradition persisted. One distinctively unique symbol of Samoan culture and identity that came under particular pressure to be abandoned was the pe’a.

The pe’a is a traditional Samoan tattoo worn by men, covering the body from torso to knees. Young men receive it as a rite of passage into adulthood. This initiation is a critical and highly ritualised event in a Samoan man’s life, signalling the transition from one stage of being—adolescence—to another, more evolved, state. Traditionally, this process takes five days (although often it can take weeks) and is extraordinarily painful: rudimentary combs of different sizes, each made up of razor-sharp teeth attached to a turtle shell attached at a right angle to a stick, are repeatedly dipped into ink and tapped into the skin using a mallet, known as iapalapa. The tufuga (tattooist) tattoos freehand without any guide to reference. The design is made up of perfectly symmetrical lines, triangles, arrows, dots, and other geometric patterns. Each element is imbued with sacred, mythological meaning, and, equally meaningfully, the tattooing begins on the spine, moves around the torso, up the hips, encapsulates the thighs and buttocks, and ends around and inside the belly button.

Chris Lemuelu's back is still visibly embossed (photo taken by www.duncographic.com).

(photo taken by www.duncographic.com).

The ritual involved serves to clearly define and give meaning to the initiation. Prior to the arrival of Europeans, the process was laden with elaborate and formalised dancing, sham fights, and wrestling matches. Affronted by the heathen revelries associated with tatau, the early Christian missionaries from 1830 onwards sought to ban tattooing and continued to apply censorship pressure up until 1920. Although this supression had varying degrees of success in different parts of the archipelago, Samoan men persistently sought opportunities to acquire tatau elsewhere throughout the islands, and it is because of their obstinacy that the ceremony exists today—albeit bereft of fights, wrestling, and dance, yet abounding with singing and musical instruments.

Christian missionaries and colonialists have a well-known history of effacing indigenous ritual and replacing it with their own ecclesiastical forms of ceremony. I believe that the effects of this practice on young, modern men unfortunately still reverberate today. You could be forgiven for thinking that many of your friends are long overdue for their transition into adulthood. I know an abundant number of grown ‘men’, who, sixty years ago, would’ve had their immaturity dismissed as a symptom of feeblemindedness. These days, however, playing video games; collecting figurines; watching cartoons; being impetuous, rambunctious, unstable, emotionally inept, socially gauche, semi-literate, and saying ‘amazeballs’ are typical and expected character traits of modern ‘men’. It’s not because they’re innately sophomoric with egos far superseding their worth. I believe the absence of a rite of passage is the cause of their perpetual adolescence, as well as the growing prestige that’s become attached to everything juvenile. Benjamin Barber, in his formative work Consumed, calls this phenomenon the infantilisation of adults, and he ascribes young men’s doltishness to capitalism, pointing out the vested interests of consumerism in keeping these adults as infantile as possible for as long as possible.

Initiation is to align individuality with generalised, stable, and meaningful social norms through physical and/or psychological travails. It is believed that men who have gone through a rite of passage are likely to be less pathological or to contest the moral and ethical code of their milieu. The declining purview of religious and institutional authority, coupled with the failure of capitalist culture in providing sacred and durable meaning for existence, has hindered the transition into adulthood. There is no commonly shared and culturally ingrained demarcation by which contemporary men may leave the proclivities of their youth behind and move ahead, armed with wisdom imparted to them by respected authoritative figures. You may disagree and rattle off numerous examples for contemporary forms of rituals performed for a change in status, yet it is difficult to offer any that embody what Arnold Van Kemp recognised in his original and seminal work, Rites Of Passage, as the three fundamental stages of an initiation: separation, transition, and incorporation. First, separation is to leave the collective identity and traverse into the unknown.

(photo taken by www.duncographic.com).

‘You’re only sitting there with the tattooist, and, the next thing you know, there are five six-foot, massive guys coming in.’

Chris Lemuelu, Samoan by descent, lives in Melbourne, Australia, and tells me about his ritualised journey from adolescence to adulthood. He is a soga’imiti, a man who has completed the full pe’a.

‘You’re there freaking out about what’s going on, because they don’t really explain to you what’s going to happen. It’s all men. These guys are important.’

(photo taken by www.duncographic.com).

Second, transition is the process of change from child to man via a symbolic death and rebirth, where the initiate comes into contact with the sacred. Chris endured nine hours of tattooing every day, from before sunrise to mid-afternoon, for five days. Any trace of adolescence was bled out of him.

‘The first hit, your mind is full of so many thoughts; mostly you’re thinking, “Shit, what have I done; what am I doing; I can’t do this”. After a few days, I couldn’t feel my body: the pain had reached a different level. I was in another world; I was literally looking over my own body. I was simply not there.’

After experiencing the pseudo-death, one is reborn into adulthood. This transmogrification was represented through the cracking of an egg on the Chris’ head, which symbolised rebirth.

‘Although at the end of it I couldn’t even bend my knees, because the tattoo was so tight, I felt like The Man. I had never been so emotional before in my life. Throw a chair at my head—I can handle anything.’

His bravado was put to the test several days after the ceremony, at an island resort where he was holidaying with his girlfriend.

‘I wanted my girl to have a good time and relax a bit. But I wasn’t eating—I couldn’t, for three days after the tattoo. When you think about it, the amount of blood cells that travel around your body every second: imagine the amount of ink added to that as it goes to your heart. I couldn’t sleep on a bed because everything was sticking—you’re pretty much an open wound. At one stage I went for a walk, and twenty-four hours later I woke up with intravenous drips coming out of me.’

Having passed out, he had been admitted to hospital. Such was the dire state of his body, he needed adrenalin shots to accomplish the simple task of showering. Several days later, at the Samoan international airport, while walking across the tarmac toward the plane, full of adrenalin but still in immense pain, Chris’s body gave up, and he found himself unable to move. But then, as though confirming the tufuga’s words—‘All of Samoa is with you’—an old lady came to him and carried his bags, while several large chiefs, important men, carried him into the plane and made sure he had enough water.

‘It was amazing. It was like the whole country came to help me. But that’s how strong this tattoo is.’

“Clothed not to cover your nakedness but to show you are ready for life, for adulthood and service to your community, that you have triumphed over physical pain and are now ready to face the demands of life …”

This rite of passage continues to be a crucial channel through which young Samoan men connect with their culture and identity. Although the process is voluntary, without the pe’a a Samoan male will never be considered a true man

‘You have a choice, and once you choose, it’s expected to be done, and done properly.’

It is sacrilegious, almost criminal, to have the pe’a done by someone who hasn’t inherited the title of tufuga.

‘There is no turning back once you decide to engage. It doesn’t matter who your family is, it’s really dishonourable and extremely insulting if you don’t complete it. You will be shunned and labelled a pe’a mutu, which is a mark of shame.’

Chris endured the tatau at the hands of the most respected master tattooists of Samoa and Polynesia: father and son Petelo and Peter Sulu’ape. Samoa is still very much a hierarchical society, and the tattoo is used to reinforce an existing order. By receiving the pe’a, Chris became established as a man of status within his community: it marked out his standing in his family, and, as often happens, the pe’a also represents his patrilineal claim to land. The third and final stage of initiation, incorporation, Van Kemp observed, refers to the initiate re-entering society endowed with a new recognised social status.

(photo taken by www.duncographic.com)

‘People know that I’ve been through the ritual of pain and tradition. In a sense, you’re seen as having died—gone through the worst pain. I’m treated well; people make sure I’m there at the table eating food first. Now I have the right to make important decisions for my family and my village. I make decisions my older cousins should be making, but people don’t listen to them because they’re not soga’imiti: they listen to me. Like Chuck Norris, I only have to say one word.’

As a Samoan man, living in Melbourne has placed Chris in a position to experience cross-cultural friction relating to the nature of power, and this has exposed the pe’a to challenges of relevance global forms of cultural homogenisation stimulate.

(photo taken by www.duncographic.com)

‘When I’m talking on the phone to people in Samoa I have power, but then, as soon as I hang up, I think to myself, ‘Who am I to talk to people like that?’ You can see the importance fade: it’s becoming a statement of fashion in some places. Prime example: the Samoans playing NFL and rugby. How many players have sleeves? That’s not traditional; they don’t ask themselves, “Have I studied the patterns? Do I know the difference between the soft shapes of the female tattoo and the jagged spears of the male tattoo? And what does it mean to me?” But for me, it was my degree.’

Photos taken by Duncographic.