Stick & Poking Aboard Convict Ships

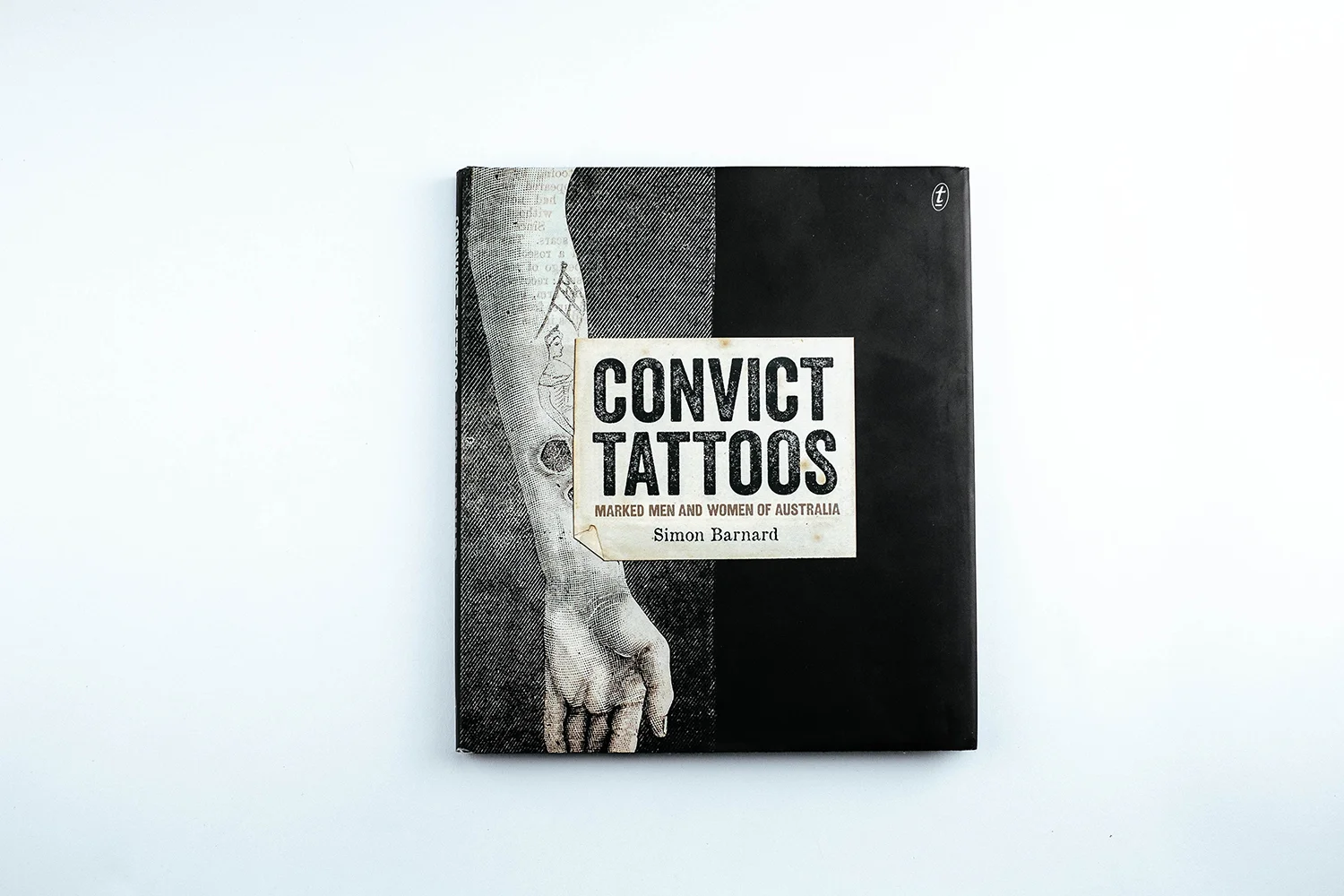

Simon Barnard’s new book, Convict Tattoos: Marked men and women of Australia

In 19th Century England, petty crimes like stealing bread would secure a sentence of ‘transportation,’ which meant, quite literally, to transport delinquents from one hell to another. Between 1788 and 1868, over 162,000 of these convicts were sent to various penal colonies across Australia, where men served sentences mostly toiling land and women through domestic servitude. The voyage was shit, but they kept busy… and upon arrival each convict was stripped and gingerly scrutinised to record defining features. As it turns out, these records still exist. And, according to Simon Barnard’s new book, Convict Tattoos: Marked men and women of Australia, they reveal what is potentially the largest typology of 19th century tattoos.

I talk with Simon about colonial Australian tattoo history and his book’s illustrative tattoo portraits.

Isaac Comer, aged 31, undergoing inspection in Hobart Town, 1845. Picture: Convict Tattoos: Marked Men and Women of Australia

May I start by asking how you came to write and illustrate a book about Australian convict tattoos?

Hi, Fareed. When convicts arrived in Australia the authorities recorded their tattoos. I’ve been into convict history for a long time, and I’ve had to read through a lot of those tattoo descriptions. I became a bit obsessed with them, I suppose. So I started researching it all and eventually amassed enough material to produce a book.

You mention in the book that it was the largest anthropological account of any group of people on the planet at that time. Is that really so? What was the research process like?

Yeah, it’s kind of a big call. Robert Hughes said it. I rolled with it. Research involved reading through thousands of records. I ended up tabulating the tattoos of over 10, 000 convicts. This allowed me to estimate how many convicts were tattooed, and which motifs were most popular. By working off these same records I was able to produce detailed drawings of the convicts—their height, visage, scars, etc. The most challenging thing was trying to find pictures of their tattoos. I got around that by studying contemporaneous pop culture—decorated snuff boxes and so-on. And preserved human skin specimens also give a good indication of how they may have looked.

Did you come across any other interesting artefacts?

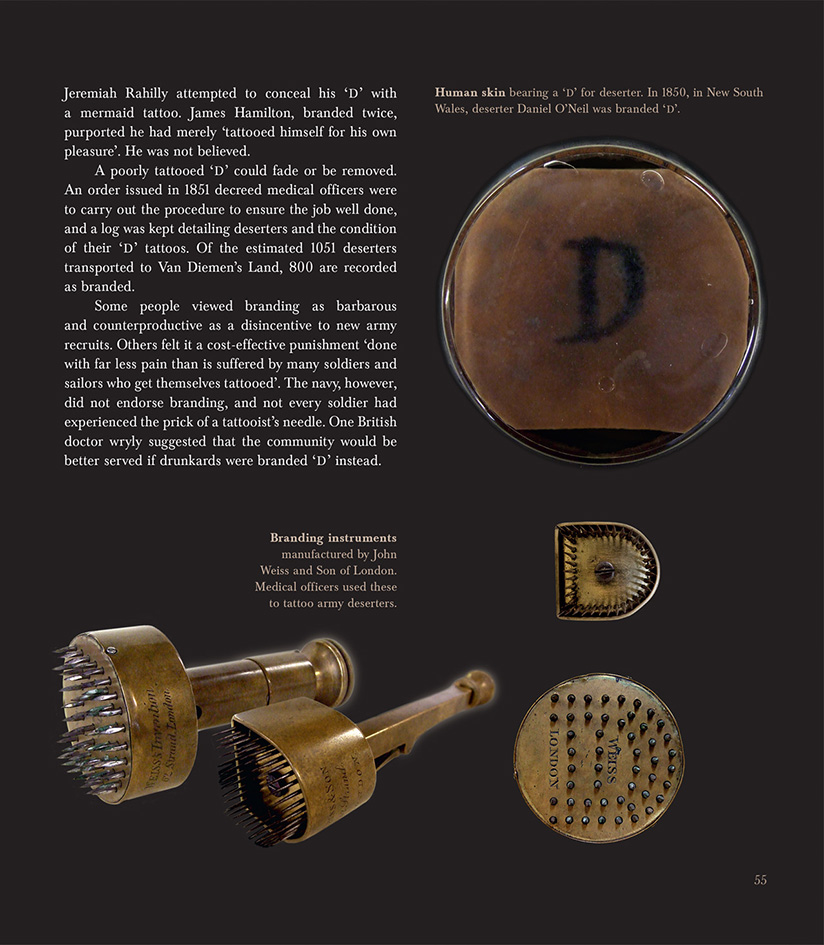

Tattoo iconography features on a wide array of stuff including love tokens, tableware, that kind of thing. I also have some cool acetate tattoo stencils that can be attributed to Professor W. M. Lyons, a prominent tattooist born in 1872, in Melbourne. But I’m pretty taken with the branding tools that were used to brand deserters with a neat little ‘D’.

D for Deserter. Picture: Convict Tattoos: Marked Men and Women of Australia

A professor tattooist? Who is this guy?

Yeah, Lyons, he was an itinerant tattooist who travelled the globe. Also termed himself ‘The King of Professional Tattooers’. What a guy!

You indicate that Australians were quite possibly the world’s most heavily tattooed English-speaking people of the nineteenth century. I’m sure many Australians would be proud of that claim. It must have been a painstaking process – combing through the records of newly arrived convicts. Can you tell me about these registers?

They’re known as the ‘black books’: big, beautiful, battered ledgers. The contents were written in 19th century copperplate; hard to read, but worth it. Each convict had their physical description recorded along with their vocation, birthplace, next of kin, and their crimes and offences, of course. This meant that convicts could be placed into suitable work, recognised among the general population, and punished or rewarded according to their behaviour.

What types of crimes led to a sentence of transportation?

All kinds. Oddball examples include sacrilege, poisoning, selling dodgy food, vagrancy, perjury and bigamy. Dennis Collins lobbed a rock at King William and was transported for life. Petty theft was the most common crime.

William Henry Stephens. Picture: Convict Tattoos: Marked Men and Women of Australia

In your book you mention tattoos weren’t popular among criminals in England nor were they popular in the penal colonies themselves, yet 37% of men and 15% of women arrived in Australia sporting tattoos. How is that so?

It would be safer to say that tattooing wasn't as popular among English criminals and the general public. But we don’t really know. Likewise with transported convicts: most convicts didn't have their tattoos recorded before they disembarked for Australia, and tattoo descriptions generally weren’t updated after they arrived. But by examining the records of convicts that shipped together it becomes clear that tattooing was extremely popular during the voyage out. At least thirty-one men who sailed aboard the Lord Lyndoch were tattooed with a mermaid, for example.

What kinds of tools were they using on the ships?

Pretty basic stuff. Pins for puncturing the skin, charcoal, ink and gunpowder as dyes.

Not very hygienic then. Were tattoo related diseases common?

Not very hygienic by today’s standards. But tattooing couldn’t have posed too much of a problem as it's not mentioned in the many rules and regulations pertaining to colonial New South Wales and Tasmania.

Human skin tattooed with a heart pierced with a dagger, and the initials P.V.VV. Believed to be French, circa. 1850-1900. Source: Convict Tattoos: Marked Men and Women of Australia. Image: Science & Society Picture Library.

Can you tell me about the iconography of convict tattoos?

Well, some of the symbolism goes way back. Mermaids, for example. But generally speaking, the motifs recorded express love, be it for Christ or one’s country or family. Names and initials were most popular, followed by anchors, people and then hearts. Some convicts were tattooed with rings and bracelets. Other convicts were tattooed with chains. Thomas Mead had the word ‘free’ tattooed across his chest. William Langham’s chest bore the words ‘catch me’ and ‘fuck me’. Alice Marsh was tattooed with a woman clutching a flower and handkerchief. Charles Woodirvis bore a birdcage.

Were there any particularly heavily tattooed convicts?

Isaac Comer, mentioned in the text, was heavily tattooed including on his cock. But another interesting example is Henry Findlay, who was tattooed on his chest, arms, hands, fingers, calves and from his knees to his groin 'after the Burmese manner’. Henry was a soldier, court-martialled in Burma, so presumably he got some pretty wild tatts during service.

I can imagine. Did you have a favourite convict story?

I dig instances where the tattoo and bearer become strangely entangled. John Pilkington, for instance, was tattooed with a heart pierced with a dart. During a game of cards in Hobart Town, Pilkington was stabbed in the heart with a knife that left a wound eight inches deep. Or like William Henry Stephens who was tattooed with a skull and bones, symbolising death. When he was executed in 1851, he requested the hangman pull back his blindfold and in doing so he presented the crowd with his very own ‘death’s head.

What about the worst tattoo you came across?

Worst tattoo? You mean naughty? Robert Dudlow had the word ‘cunt' tattooed on his hand. If anyone wants to know why, they can buy the book and find out.

Tattooed human skin, believed to be French, Circa 1850-1900. Source: Convict Tattoos: Marked Men and Women of Australia. Image: Science & Society Picture Library.

Human skin tattooed with a fouled anchor, circa 1850 - 1890. Image: Convict Tattoos: Marked Men and Women of Australia. Source: Science & Society Picture Library.

What a hardcore guy. Were there any differences between the sexes?

Men were more heavily tattooed than women, and with a greater array of imagery. Most tattooed female convicts were tattooed with initials. Women were more likely to be tattooed in less visible areas such as the shoulder or leg, but, like men, most were tattooed on their forearms. The left arm was more popular than the right, which suggests that many tattoos were self-administered.

Did the tattoos have meanings?

Most tattoos were symbolic. An anchor for hope, a heart for love, a pair of doves for fidelity. That kind of thing. But tattoos meant different things to different people. Some of the weirder ones I found include Joseph Dale’s ‘woman without a head’ and William Warren’s ‘skeleton of a mermaid’. William Farrier had the word ‘fool’ tattooed across his forehead, presumably not by choice. William Brown seems to have been tattooed with his own take on the classic Adam and Eve motif: a tree with two naked men.

An illustration of convict absconder Miles Confrey. Picture: Convict Tattoos: Marked Men and Women of Australia

So tattoos weren’t a sign of criminal affiliation?

Well, I guess that’s debatable. I couldn’t find much to support that theory but there was a gang of youths known as the ‘forty thieves’ who signified their allegiance with a quincunx of dots tattooed on the webbing between the left forefinger and thumb.

Your book may become a reference for people wanting genuine convict tattoos.

That’d be nice. If anyone wants a convict-style tattoo contact Text Publishing and I’ll design you one for nuthin.

Might take you up on that offer! Do you have tattoos yourself?

You’d have to check my record to find that out.